Drinking tea on a regular basis may help protect patients with existing cardiovascular disease, according to a study in the May 7 issue of Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, which finds that tea consumption is associated with an increased rate of survival following a heart attack.

�The health benefits of tea have been reported in numerous studies in recent years, but among healthy individuals the evidence [of tea 's benefits] is actually mixed,� notes the study�s lead author Kenneth J. Mukamal, MD, MPH, of the Division of General Medicine and Primary Care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. �The greatest benefits of tea consumption have been found among patients who already have cardiovascular disease.�

Mukamal and his co-authors found that among individuals who had suffered heart attacks, those who reported being heavy tea drinkers had a 44 percent lower death rate than non-tea drinkers in the three-and-a-half years following their heart attacks, while moderate tea drinkers had a 28 percent lower rate of dying when compared with non-tea drinkers.

The key to this protection appears to lie with a group of antioxidants known as flavonoids, which are plentiful in both black and green tea. Flavonoids, which are also found in certain fruits and vegetables, including apples, onions and broccoli, could be working to help the heart in one of several ways, according to Mukamal.

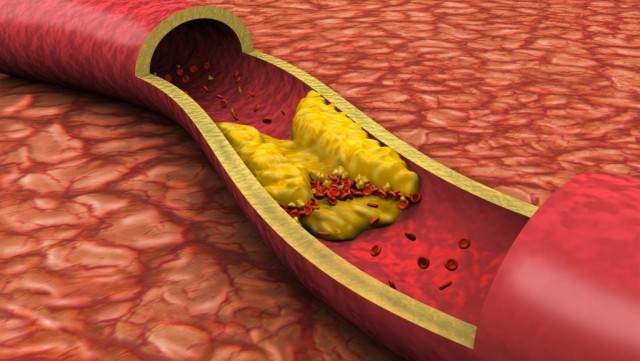

�It's pretty clear that flavonoids can prevent LDL [low density lipoprotein] cholesterol from becoming oxidized,� he says, explaining that oxidized LDL can lead to the development of atherosclerosis. In addition, a recent study found that drinking black tea improved endothelial function � the ability of the blood vessels to relax � in cardiac patients. Finally, he adds, flavonoids may have an anti-clotting effect.

Continue Reading Below ↓↓↓

The observational study was made up of 1,900 individuals, both men and women mainly in their 60s, who were questioned by trained interviewers an average of four days after suffering a heart attack and asked to report how much caffeinated tea they typically drank each week. The participants were then separated into three groups: non-drinkers, moderate tea drinkers (fewer than 14 cups per week) and heavy tea drinkers (14 or more cups per week).

Based on these criteria, 1,019 patients were categorized as nondrinkers; 615 were moderate tea drinkers; and 266 were considered to be heavy drinkers. The patients were followed up 3.8 years later, at which time 313 individuals had died, mainly from cardiovascular disease. After accounting for differences in age, gender, and clinical and lifestyle factors, the researchers found an inverse relationship between tea consumption and mortality.

�What was surprising was the magnitude of the association,� says Mukamal. �The heaviest tea drinkers had a significantly lower mortality rate than non tea-drinkers.�

As is the case with any observational study, he notes, these findings could be accounted for by differences in lifestyle other tea drinking. �One of the biggest potential criticisms of this study is that people who drink tea might be expected to live healthier lifestyles than people who don�t drink tea,� he explains. �But among this particular group � people mainly in their 60s who had suffered heart attacks � tea consumption was not strongly related to lifestyle.� In other words, the participants were similar in terms of education, income, exercise habits, and smoking and drinking habits whether they drank a lot of tea or no tea at all.

Mukamal does caution, however, that although these findings strongly suggest that tea consumption reduces the risk of death following a heart attack, controlled clinical studies will need to be conducted to firmly establish the link.

The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and from the American Heart Association. Study co-authors include Malcolm Maclure, ScD, and Jane B. Sherwood, RN, of the Harvard School of Public Health; James E. Muller, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital; and Murray A. Mittleman, MD, DrPH, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Source: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center