Researchers from Mount Sinai School of Medicine have discovered a novel function of brain insulin, indicating that impaired brain insulin action may be the cause of the unrestrained lipolysis that initiates and worsens type 2 diabetes in humans. The research is published this month in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Led by Christoph Buettner, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, the research team first infused a tiny amount of insulin into the brains of rats and then assessed glucose and lipid metabolism in the whole body. In doing so, they found that brain insulin suppressed lipolysis, a process during which triglycerides in fat are broken down and fatty acids are released.

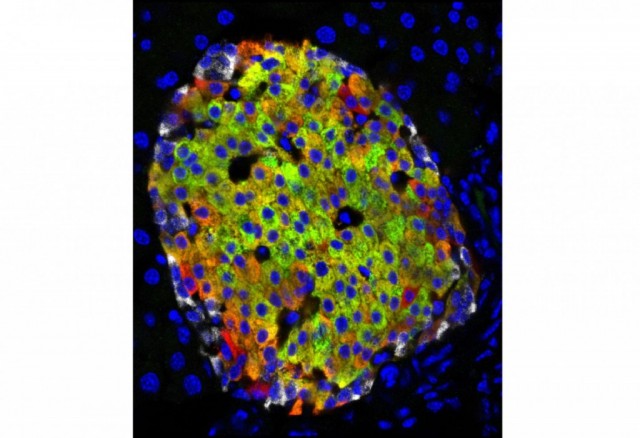

Furthermore, in mice that lacked the brain insulin receptor, lipolysis was unrestrained. While fatty acids are important energy sources during fasting, they can worsen diabetes, especially when they are released after the person has eaten, as happens in people with diabetes. Researchers previously believed that insulin's ability to suppress lipolysis was entirely mediated through insulin receptors expressed on adipocytes, or fat tissue cells.

"We knew that insulin has this fundamentally important ability of suppressing lipolysis, but the finding that this is mediated in a large part by the brain is surprising," said Dr. Buettner.

"The major lipolysis-inducing pathway in our bodies is the sympathetic nervous system and here the studies showed that brain insulin reduces sympathetic nervous system activity in fat tissue. In patients who are obese or have diabetes, insulin fails to inhibit lipolysis and fatty acid levels are increased. The low-grade inflammation throughout the body's tissue that is commonly present in these conditions is believed to be mainly a consequence of these increased fatty acid levels."

Continue Reading Below ↓↓↓

Dr. Buettner added, "When brain insulin function is impaired, the release of fatty acids is increased. This induces inflammation, which can further worsen insulin resistance, the core defect in type 2 diabetes. Therefore, impaired brain insulin signaling can start a vicious cycle since inflammation can impair brain insulin signaling."

This cycle is perpetuated and can lead to type 2 diabetes. Our research raises the possibility that enhancing brain insulin signaling could have therapeutic benefits with less danger of the major complication of insulin therapy, which is hypoglycemia."

Dr. Buettner's team plans to further study conditions that lead to diabetes such as overfeeding to test if excessive caloric intake impairs brain insulin function. A major second goal will be to find ways of improving brain insulin function that could break the vicious cycle by restraining lipolysis and improving insulin resistance.

This study is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and the American Diabetes Association. First author of the study is Thomas Scherer, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Medicine in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease.

Source: The Mount Sinai Hospital / Mount Sinai School of Medicine