September 2005 - Episodes of dangerously low blood glucose, or hypoglycemia, were greatly reduced in people who received an islet transplant for poorly controlled type 1 diabetes, according to an analysis of outcomes in 138 patients who had the procedure at 19 medical centers in the United States and Canada. This is one of the conclusions of the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR), which tracks many factors affecting the success of this experimental procedure in people with severe type 1 diabetes. The CITR, funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), released its second annual report (www.citregistry.org) today.

In islet transplantation as performed by the centers, clusters of insulin-producing cells, called islets, are extracted from a donor pancreas and infused into the portal vein of the recipient's liver. In a successful transplant, the islets become embedded in the liver and begin producing insulin. Islet transplantation (http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/pancreaticislet/index.htm) is an experimental procedure reserved for people with severe or complicated type 1 diabetes. Because of the risks associated with islet transplantation, patients chosen for the procedure were those who had the greatest need and potential for benefit, such as those with a history of hypoglycemia unawareness.

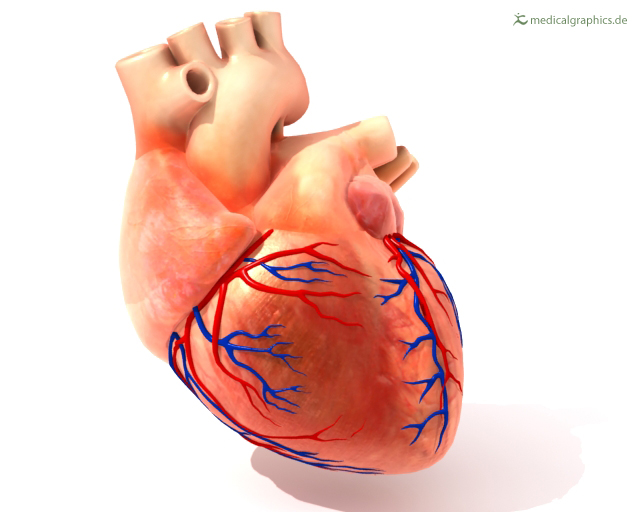

Type 1 diabetes, which affects up to 1 million people in the United States, develops when the body's immune system destroys the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. This form of diabetes usually strikes children and young adults, who need several insulin injections a day or an insulin pump to survive. Insulin is not a cure, however. Eventually, most people with type 1 diabetes develop one or more complications of the disease, including damage to the heart and blood vessels, eyes, nerves, and kidneys.

Most people with type 1 diabetes know the signs of low blood glucose and take steps to counteract it before their glucose dips further and leads to a loss of consciousness. However, some patients with brittle or difficult-to-control diabetes, who can't sense that their blood glucose is too low, may lose consciousness anywhere and without warning. Nearly all patients receiving a transplant had severe hypoglycemia episodes requiring another person's help before the transplant, but such events are very rare in the year after a successful transplant, the CITR reports. One infusion of islets, though not always enough to keep blood glucose in the normal range, generally lowered insulin needs and alleviated episodes of severely low blood glucose in most patients.

One year after the last infusion, 58 percent of recipients no longer had to inject insulin. Those who still needed insulin a year after their last infusion had a 69 percent reduction in insulin requirements. However, in 19 recipients followed by the registry, the donor islets failed to function. Transplant failures, as measured by blood glucose levels and confirmed by a test of C-peptide, occurred as early as 30 days after the recipient's first islet infusion to more than 2 years after the last infusion.

Eighteen of the 19 centers contributed data on adverse events, including 77 serious adverse events. About 58 percent of the serious events required inpatient hospitalization, and 22 percent were considered life threatening. Seventeen percent of the serious events were linked to the islet infusion procedure (e.g., infection or bleeding), and 27 percent were related to medications that suppress the immune system (e.g., anemia, nerve damage, and low numbers of white blood cells). Recipients received immunosuppressive drugs that usually included daclizumab at the beginning of the procedure to prevent immune rejection of donor islets, then sirolimus and tacrolimus to maintain immunosuppression.

"The registry is still quite young, but it's doing a very good job of providing critical information on the results of islet transplantation," said Dr. Michael Appel, who oversees the project for the NIDDK. "As the registry matures, researchers will be able to use the data to identify factors that increase risk and those that promote success. This information will help centers refine their protocols based on objective information."

Centers' participation in the CITR is voluntary. The registry's second report gives information on donor and patient characteristics, pancreas procurement and islet processing, immunosuppressive medications, functional potency of the donor islets, patients' lab results, and adverse events. "We're getting critical information on the factors that influence the success of islet transplantation," said Dr. Rodolfo Alejandro, director of Clinical Islet Transplantation at the University of Miami's Diabetes Research Institute.

Recipients had type 1 diabetes an average of 29 years before the transplant. Most � 118 � received an islet transplant alone. An additional 19 patients had an islet transplant after receiving a kidney transplant. One patient received an autograft transplant of his own islets that were extracted after pancreatic surgery and then infused into the liver. Forty patients received one islet infusion, 69 received two, and 28 received three. A single patient received four infusions.

Recipients, 66 percent of whom were women, were an average age of 42 years (range 24 to 64 years). Their average weight was in the healthy range. Before the procedure, nearly half the recipients were using an insulin pump. Their average level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which reflects blood glucose control over the previous 3 months, was 7.6 percent, compared to a normal HbA1c of 6 percent. HbA1c levels generally improved with each infusion, as did levels of C-peptide, a measure of insulin secretion.

"The registry is disseminating much needed data on the safety and efficacy of islet transplantation to investigators, health care professionals, providers, payers, and patients. We believe that the registry will contribute to a better understanding of trends in islet transplantation," said Dr. Bernhard Hering of the University of Minnesota, CITR's Medical Director and Chair of its Scientific Advisory Committee. Hering is a participating investigator in NIH-funded studies, scheduled to begin early next year, that aim to improve the safety and efficacy of islet transplantation: http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/oct2004/niddk-04.htm.

The CITR's mission is to expedite progress and promote safety in islet transplantation by collecting, analyzing, and communicating data on islet transplantation. NIDDK established the registry in 2001 through a contract awarded to the EMMES Corporation. The CITR is one of the projects made possible by a special funding program awarded by the Congress to HHS for type 1 diabetes research. For a description of projects funded by this program, see http://www.niddk.nih.gov/federal/planning/type1_specialfund/.

From 1990 to 1999, only 8 percent of islet transplants resulted in insulin independence for more than 1 year. In 2000, however, a group of researchers led by Dr. James Shapiro at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, reported much greater success in patients transplanted with higher numbers of islets and treated with an immuno-suppressive regimen that omitted glucocorticoids, now thought to be toxic to islets. In the next few years, other researchers replicated the Canadian team's "Edmonton protocol," and many centers have adopted this approach to islet transplantation, with some modifications.

The scarcity of islets poses a major obstacle to wider testing of islet transplantation as a treatment for type 1 diabetes. Organs from about 7,000 deceased donors become available each year. Because of the fragility of the pancreas, only about 3,500 pancreata are suitable for transplantation, and many of these organs are used for whole organ transplantation. To improve the potential of cell replacement therapy for diabetes, NIH-funded research is focusing on understanding the insulin-producing beta cell and its regeneration and on efforts to develop alternative sources of beta cells. Researchers are also working on ways to coax the immune system into accepting donor cells or tissues without suppressing the whole immune system.

Because of islet scarcity and the risks associated with the procedure and lifelong immunosuppression, islet transplantation is not being tested as a treatment for most people with type 1 diabetes. Nor is it being tested in type 2 diabetes, the most common form of diabetes. People with this form of diabetes are less likely to suffer from severe swings in blood glucose and hypoglycemia unawareness. Moreover, islet transplantation cannot correct insulin resistance, an underlying disorder of type 2 diabetes that is marked by the inability of cells to use insulin effectively.

Single copies of the CITR report may be ordered free of charge from the registry (www.citregistry.org) or from NIDDK's National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse at 1-800-860-8747.

Source: CITR