People with type 1 diabetes show signs of accelerated aging and slower information processing. Study suggests that middle-aged type 1 diabetics should be screened for cognitive difficulties.

The brains of people with type 1 diabetes show signs of accelerated aging that correlate with slower information processing, according to research led by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

The findings indicate that clinicians should consider screening middle-aged patients with type 1 diabetes for cognitive difficulties. If progressive, these changes could influence their ability to manage their diabetes. The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is online and will be published in the May 19 issue of the journal Neurology.

“The severity of cognitive complications and cerebral small vessel disease — which can starve the brain of oxygen — is much more intense than we expected, but it can be measured in a clinical setting,” said senior author Caterina Rosano, M.D., M.P.H., associate professor in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Epidemiology.

Rosano added that “Further study in younger patients is needed, but it stands to reason that early detection and intervention — such as controlling cardiometabolic factors and tighter glycemic control, which help prevent microvascular complications — also could reduce or delay these cognitive complications.”

Type 1 diabetes usually is diagnosed in children and young adults and happens when the body does not produce insulin, a hormone that is needed to convert sugar into energy.

Continue Reading Below ↓↓↓

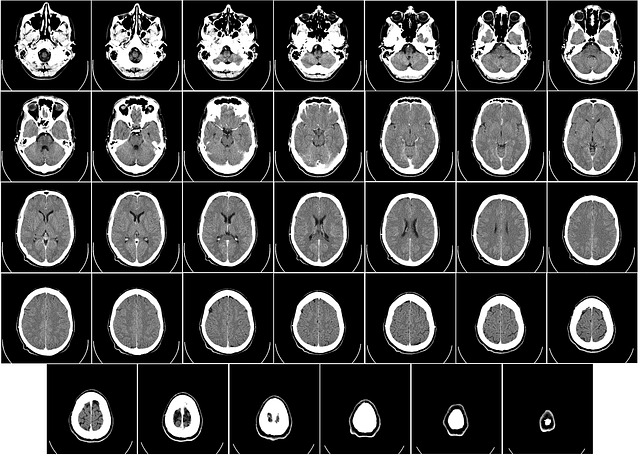

Dr. Rosano and her co-authors examined brain MRIs, cognitive assessments, physical exams and medical histories on 97 people with type 1 diabetes and 81 of their non-diabetic peers.

The people with type 1 diabetes were all participants in the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study, an ongoing investigation led by Pitt Public Health epidemiologist and study co-author Trevor Orchard, M.D., to document long-term complications of type 1 diabetes among patients diagnosed at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC between 1950 and 1980.

The MRIs showed that 33 percent of the people with type 1 diabetes had moderate to severe levels of white matter hyperintensities (markers of damage to the brain’s white matter, present in normal aging and neurological disorders) compared with 7 percent of their non-diabetic counterparts.

On three cognitive tests that measure abilities such as information-processing speed, manual dexterity and verbal intelligence, the people with type 1 diabetes averaged lower scores than those without the condition.

Among only the participants with type 1 diabetes, those with greater volumes of white matter hyperintensities averaged lower cognitive scores than those with smaller volumes, though the difference was less pronounced.

The associations held even when the researchers adjusted for high blood pressure and glucose control, which are conditions that can worsen diabetes complications.

The study identified signs of nerve damage, such as numbness or tingling in extremities, as a risk factor for greater volumes of white matter hyperintensities.

“People with type 1 diabetes are living longer than ever before, and the incidence of type 1 diabetes is increasing annually,” said lead author Karen A. Nunley, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow in Pitt Public Health’s neuroepidemiology program. “We must learn more about the impact of this disease as patients age. Long-term studies are needed to better detect potential issues and determine what interventions may reduce or prevent accelerated brain aging and cognitive decline.”

Additional authors on this study are Christopher M. Ryan, Ph.D., Howard J. Aizenstein, M.D., Ph.D., J. Richard Jennings, Ph.D., John Ryan, Ph.D., Janice C. Zgibor, R.Ph., Ph.D., Robert M. Boudreau, Ph.D., Tina Costacou, Ph.D., and Rachel G. Miller, M.S., all of Pitt; and John D. Maynard, M.S., of VeraLight Inc.

This research was supported by NIH grants R01 DK089028, R01 DK034818-25 and R01 HL101959.

Continue Reading Below ↓↓↓

Source: University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences