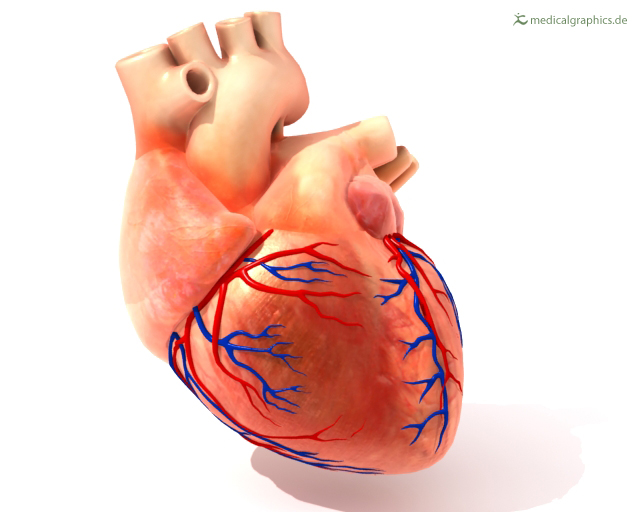

Promising results from a study of therapeutic angiogenesis - an experimental treatment involving the injection of a gene product designed to produce a protein that promotes blood vessel growth in the heart - may translate into a future treatment option for some of the nearly 7 million people nationwide who suffer from debilitating chest pain caused by coronary artery disease. The University of Vermont was one of twelve sites participating in the Angiogenic Gene Therapy (AGENT) trial, the first trial of intracoronary gene therapy, and enrolled the initial patient in this study. A report on the study will appear in today's issue of Circulation: A Journal of the American Heart Association.

"Coronary artery disease is the number-one cause of death in Vermont, the United States and recently - the world," said Matthew Watkins, M.D., a cardiologist and associate professor of medicine who led the study at the University of Vermont site and is one of the lead authors of the report. Patients with coronary artery disease often experience angina - chest pain that results when the heart muscle doesn't get as much oxygen as it needs due to blockage in the arteries. The American Heart Association reports that 400,000 new cases of what is referred to as "stable angina" are diagnosed each year.

Currently available treatment options for coronary artery disease include drug therapy, angioplasty and bypass surgery. A non-surgical treatment, therapeutic angiogenesis is performed via catheterization - the insertion of a tiny tube into the blood vessels surrounding the heart. For this experimental therapy, a product called growth factor gene is then delivered through the tube into the coronary arteries.

A total of 79 patients between the ages of 30 and 75 years old diagnosed with mild to moderately severe stable angina participated in the first phase of the AGENT study. The study was randomized, placebo-controlled and double-blind, which means that none of the patients or investigators knew who received the active therapy until the end of the study. There were 19 participants in the placebo control group - who underwent catheterization but did not receive the active therapy - and 60 participants in the active group who did receive the therapy.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, patients underwent exercise treadmill testing at 4 weeks and 12 weeks following treatment. Patients who received therapeutic angiogenesis showed a larger improvement in exercise ability compared to those patients in the placebo group. The therapy appeared to be safe and well tolerated with no major adverse effects. A follow-up study designed to examine whether or not therapeutic angiogenesis specifically improved blood flow in obstructed areas of the heart has just completed the treatment and observation phase. According to Watkins, a preliminary analysis of the 50 patients involved in that trial also indicated favorable results.

Continue Reading Below ↓↓↓

"This research has taken an initial, but significant, step in a new direction in the treatment of coronary artery disease," Watkins said. "It leads towards a treatment, which does not involve a mechanical solution or standard drug therapy, that may be of particular benefit to patients with chronic angina who are not good candidates for additional angioplasty or bypass surgery. We are encouraged by these results and look forward to the findings from the Phase 3 trial."

The large-scale, international Phase 3 study of the effects of therapeutic angiogenesis recently launched. In this phase of the study, the goal is to confirm treatment effectiveness across a wider sample of patients with coronary artery disease. Overall, the Phase 3 study will enroll 500 patients in the United States and 500 patients in Europe and Canada.

The University of Vermont recently enrolled the first participant in the Phase 3 trial and hopes to enroll up to 30 patients over the next year. Coronary artery disease patients who are between 30 and 75 years old who suffer from angina and are not optimal candidates for bypass surgery or angioplasty may be eligible to participate.

Source: The University of Vermont